Harold Larwood was a great who was made out to be a villain - the

perfect replacement for Robin Hood in the eyes of a young ten-year-old

My father would regale us with tales of Robin Hood and his Merry Men battling the sheriff of Nottingham. I loved hearing how this ragtag bandit took on the government, robbing from the rich to give to the poor. He was a true hero, whether he existed or not, and beloved by the common man. I read Robin Hood books, watched the swashbuckling Errol Flynn film, and never missed an episode of the hit 1980s TV series.

Around the age of ten, when I put down my bow and started playing cricket more seriously, the fable of the Hooded Man naturally transformed into the folk tale of Harold Larwood.

The teenage Notts miner, the skinny lad who walked the same soot-stained streets around the pit towns of Mansfield as my father and grandfather, would go on to be the most infamous England fast bowler in history. Once my father, a talented allrounder, realised I was developing a love for cricket, the legend of Larwood was lovingly passed down the Hogg family line.

A deeper fascination with "our" home-grown speed demon was piqued by Bodyline, the TV miniseries that dramatised the 1932-33 Ashes in Australia - including the customary dodgy acting involved in recreating cricket matches. Hugo Weaving was imperious as the driven, manipulative and icy Douglas Jardine, alongside Jim Holt's deferential yet gritty Larwood. Such was the influence of this show, I even began practising, just as Larwood had done, by bowling down the alley at a dustbin as rapidly as I could. For the next few years, and perhaps even now, on the cusp of my 41st birthday, I'm still told not to try and bowl too fast.

I blame Larwood for any loss of control when I try to throw one down quicker than I can. England 1950s paceman Frank "Typhoon" Tyson put the need for speed most eloquently: "To bowl quick is to revel in the glad animal action, to thrill in physical prowess and to enjoy a certain sneaking feeling of superiority over the other mortals who play the game".

"Other mortals" - this is perhaps the source of reverence for the fast bowler: that here is a man who can physically dominate and intimidate at the wicket. There are big-hitting batsmen who impose their presence by thumping the ball back over the pavilion roof - England bowler Matthew Hoggard admitted to having nightmares about Australian bully Matthew Hayden - but none truly threaten like the express paceman.

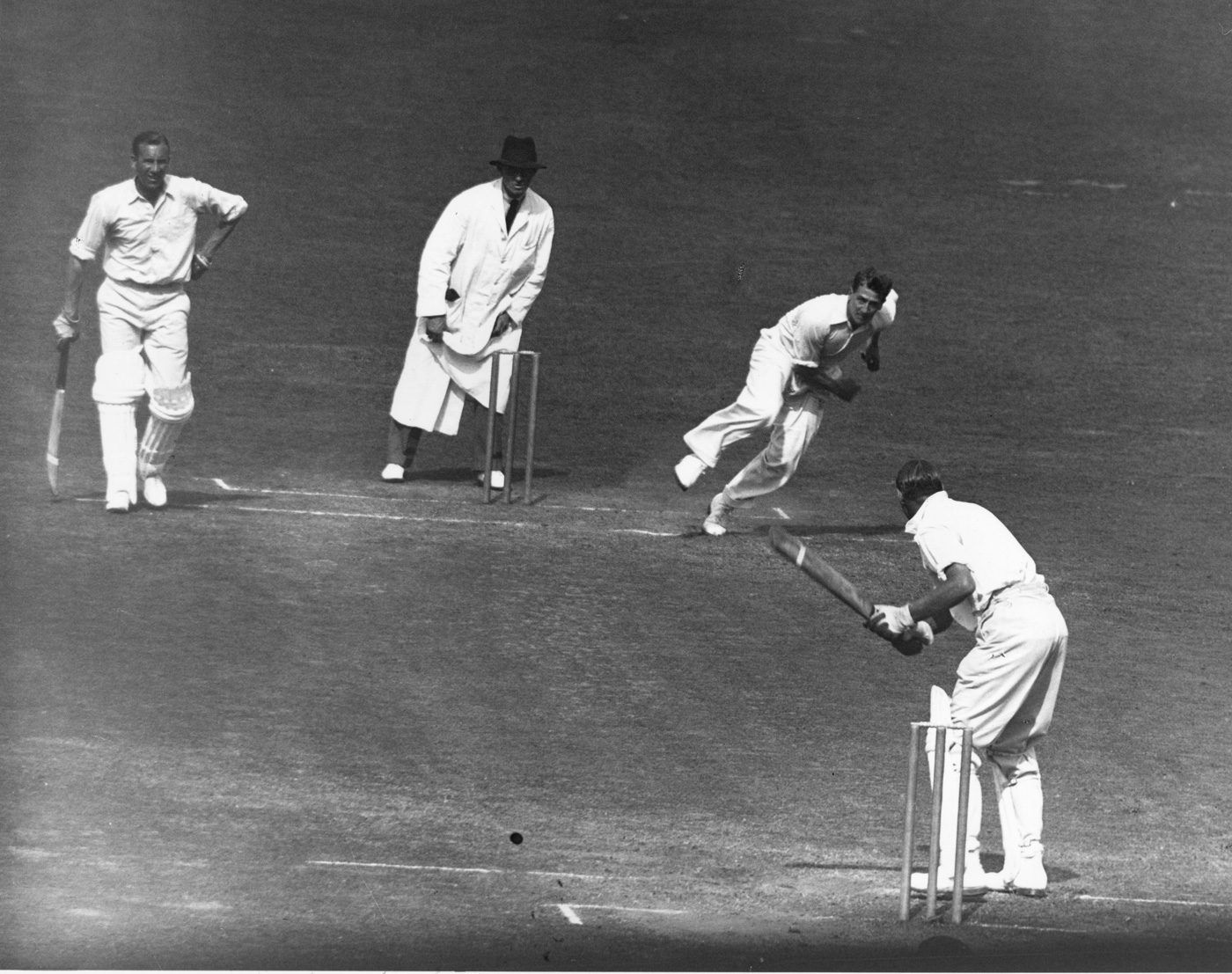

Born in 1974, I never saw Larwood play, or even met him. What I do have to flesh the ghost of my favourite cricketer is YouTube. The black-and-white footage is grainy, and with no zoom lens available, we see Harold running in to bowl from the distance of a spectator, or a boundary fielder. Still, the fabled "carpet-slippered" approach, the high left arm and absolute balance into the delivery stride, are evident. Certain clips you can't follow the ball, the black smudge on the grey background. But there's a beautiful slow-motion shot of one of his bouncers, still rising when it smacks into Les Ames' gloves.

In Duncan Hamilton's William Hill prizewinner Harold Larwood, he describes how Nottingham coach James Iremonger, "a hardened sportsman", moulded the raw talent of the scrawny pit boy into a "weapon". Stripping Larwood's action down, Iremonger straightened his run-up, pulled his shoulders back, stressed the importance of balance, and instilled a sense of discipline that included sleeping with the bedroom window open, even in the depths of winter.

What Iremonger did with Larwood in the 1920s would have personal relevance for me over 80 years on. Two seasons ago, when the Larwood fairy tale turned to hard fact when I read Hamilton's touching and eloquent autobiography, I changed my bowling action. Hamilton, like Iremonger, stripped Larwood's action - this time to the page. Once I put down the book I lifted up my arm higher, ran in on my toes, and relaxed my shoulders.

Was I any faster? Probably not, but this was the action I bowled with on a bright August day at the end of 2013, when the Authors Cricket Club, a team of cricket-playing writers I revived with literary agent Charlie Campbell, played on Larwood's old Nuncargate pitch. With that shiny red cherry between my fingers I strode in from the Larwood end, just as my grandfather and father had done before. I was the third generation of Hoggs to tread in Harold's carpet slippers - although in his early days, before the Iremonger overhaul, the long-off boundary hedge had had a gap sheared through it so the young tyro could fit in his galloping run.

Perhaps I'm letting my imagination get the better of me here, but as I ran in I could clearly picture the young Harold hurling thunderbolts. I wonder if this was his purest cricket. Before leg theory and Bodyline. Before the MCC pressed him to sign a letter apologising for bowling at the Australians, an apology that he refused to sign.

Larwood wasn't going to be the establishment's scapegoat, and he never played for England again. In a late interview Fred Trueman asked if he ever regretted not apologising. "No," Larwood replied curtly. "I had nothing to apologise for."

Banishment followed a jubilant homecoming. From a series-winning bowler to the owner of a failing Blackpool sweet shop, Larwood was an exile after his cricket life. Geoff Boycott describes the tale as "one of the saddest stories in cricket", and it took an old enemy, Jack Fingleton, to pluck Larwood from sweet-counter obscurity by offering to help him and his family move to Australia. Here, in a quiet Sydney suburb, he grew old gracefully, just as he had bowled. He reminisced about the glory days with his collection of newspaper cuttings and memorabilia, and welcomed cricketers and journalists into his home like visiting pilgrims.

Last time I travelled up to Nottingham my father met me at the station. Before he even said hello he told me that 20,000 people had met Larwood off the train after he returned from the Bodyline tour: 20,000 locals, working men who had finished backbreaking shifts down mines or in factories, had waited in a cold and damp night, clambering up walls and scaling gas lamps, for a glimpse of Lol, their hero.

Nicholas Hogg is a co-founder of the Authors Cricket Club. His first novel, Show Me the Sky, was nominated for the IMPAC literary award.

0 comments:

Post a Comment